IBS Is No Longer a Mystery: How Root-Cause Care Can Restore Gut Health

Get Personalized Insights

IBS Is No Longer a Mystery: How Root-Cause Care Can Restore Gut Health

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), also known as spastic colitis, is one of the most common reasons for visiting a doctor. Today, approximately 1 in 6 people suffer from this disorder of the large intestine [1].

The most frequent symptoms include abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhoea, constipation, and mucus in the stool.

It is a chronic, relapsing condition which, although not life-threatening, significantly impairs the quality of life of those who experience it.

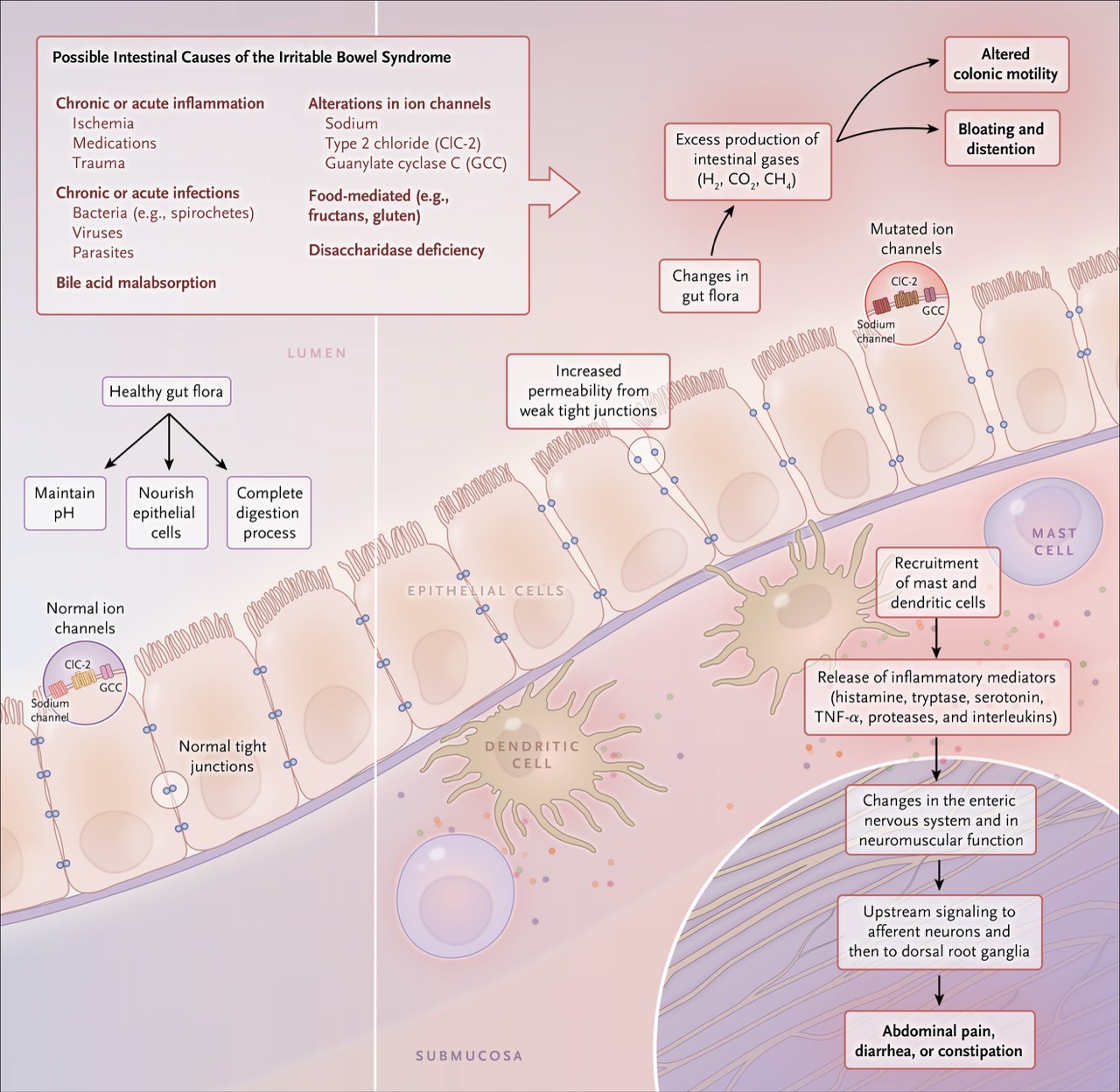

The main factors involved in the development of irritable bowel symptoms are:

- Changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiome

- Consumption of foods that promote fermentation and increased gas production

- Development of local inflammation in the intestinal wall

- Disturbance of normal intestinal motility, leading to spasms, diarrhoea or constipation, abdominal distension, and pain

People who experience the above symptoms may need to undergo diagnostic testing to exclude other pathological conditions.

However, in the majority of cases, no specific disease is identified. Irritable bowel syndrome does not cause structural changes in the intestinal tissues and does not increase the risk of colon cancer [2].

In most cases, a significant proportion of symptoms can be controlled with therapuetic interventions targeting diet, lifestyle, and specific deficiencies in the body [2–10].

A small percentage of patients with more intense symptoms may require medication for symptom relief [2].

Causes

Irritable bowel syndrome results from multiple contributing factors. However, one key mechanism is considered dominant in the development of most symptoms: a disorder in the function of the cells that line the inside of the intestine.

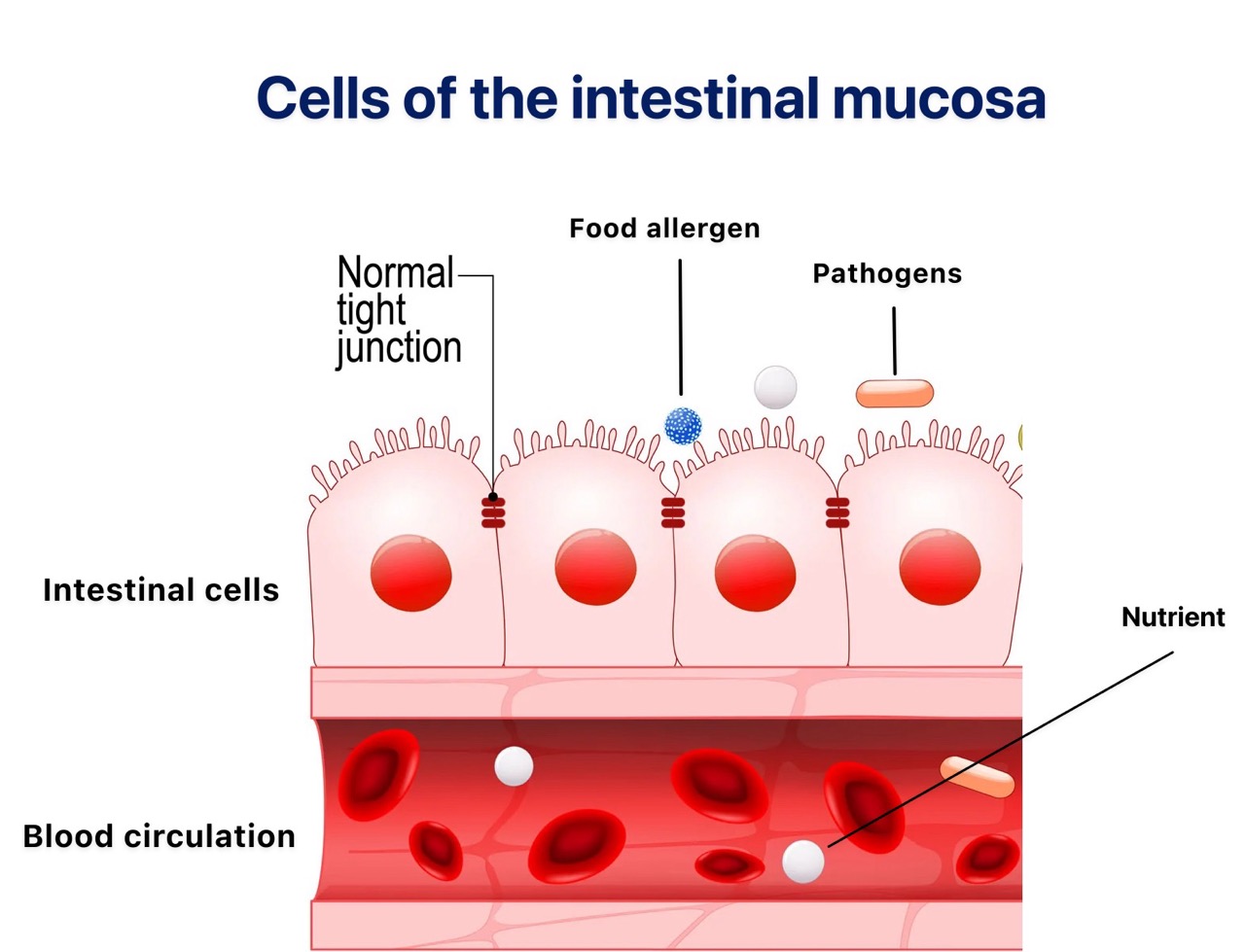

Function of the Intestinal Mucosa

The intestinal mucosa is lined with epithelial cells, which are connected by specialised junctions known as “tight junctions” or “strong bonds.” These junctions hold the epithelial cells together, maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier.

Under normal conditions, the mucosa acts as a barrier between the intestinal contents and the bloodstream.

Substances in the intestine do not pass freely through this barrier. The tight junctions between epithelial cells prevent chemicals, bacteria, drugs, and food allergens from entering the bloodstream, thereby protecting the body from harmful elements that reach the intestine.

Epithelial cells perform two essential functions:

- Selective absorption of nutrients that are beneficial to the body, allowing their transport from the intestine into the blood.

- Prevention of harmful substances and pathogenic microbes from entering the bloodstream.

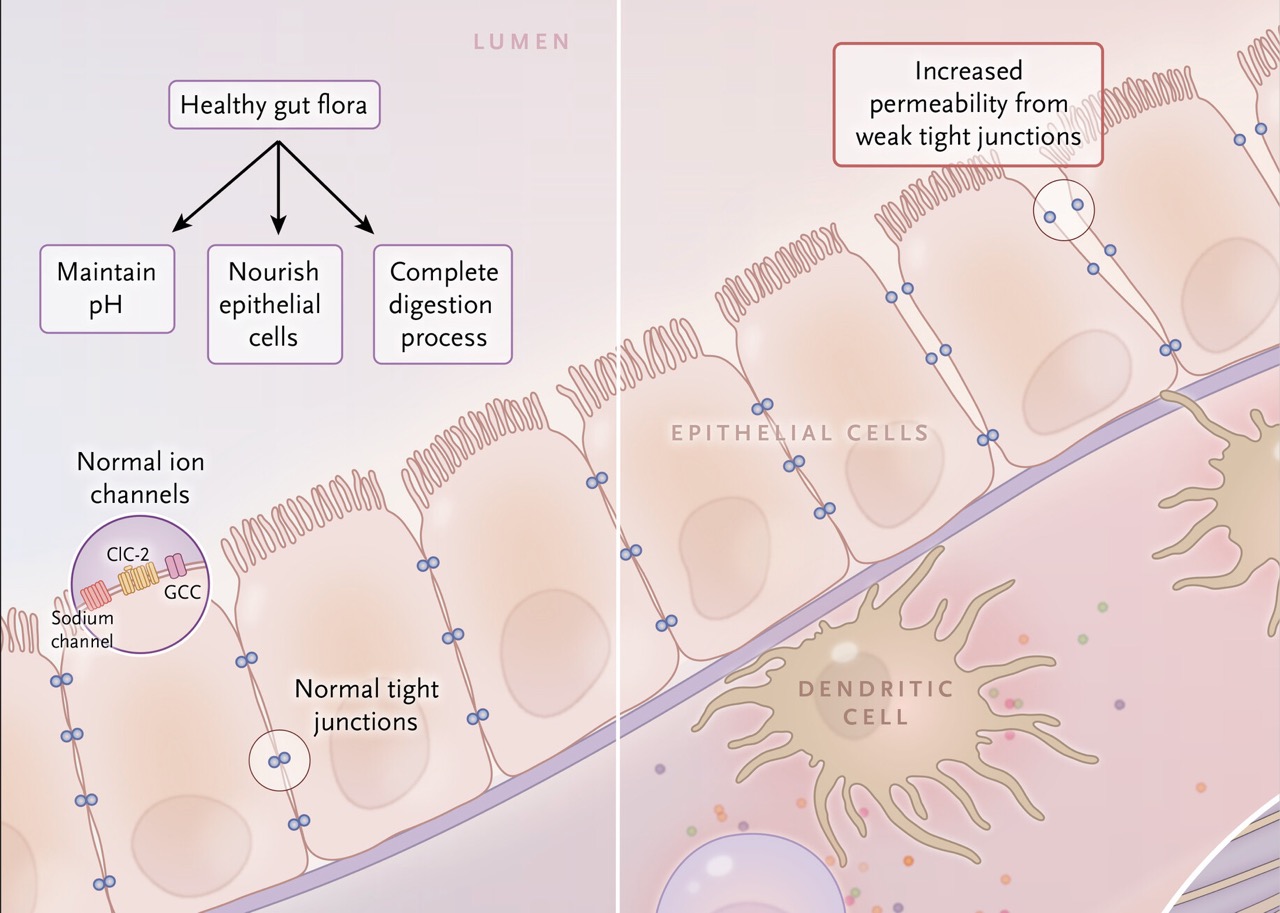

The community of microorganisms that inhabit the intestine is known as the intestinal flora (microbiota).

It plays a crucial role in nourishing epithelial cells, completing digestion, and regulating the broader intestinal environment.

How Damage to the Intestinal Mucosa Occurs

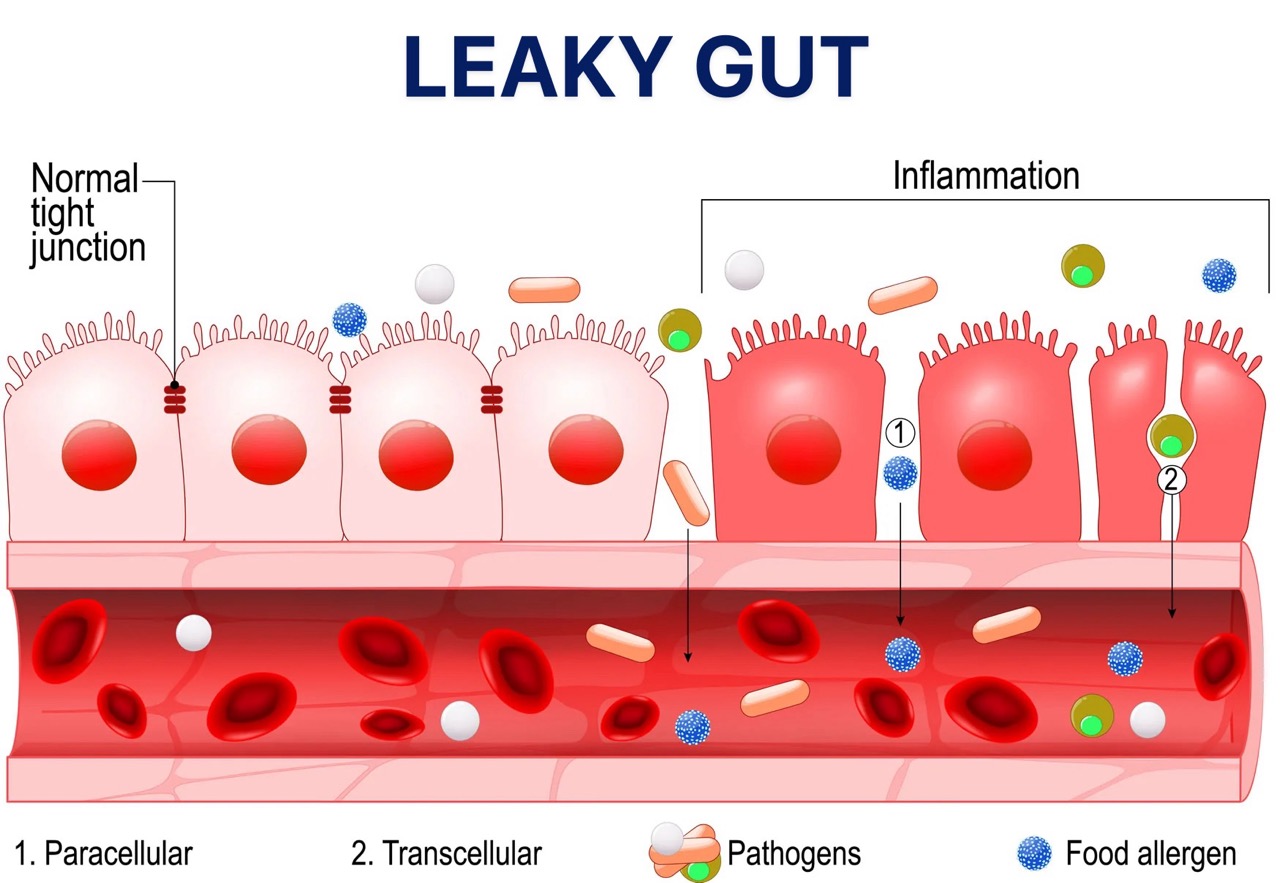

Certain foods—such as those containing gluten or specific sugars that are difficult to digest—promote the growth of pathogenic microbes. In susceptible individuals, these microbes damage the tight junctions that connect epithelial cells [11].

When these tight junctions are damaged, the intestinal mucosa loses its cohesion, allowing microbes, allergens, and chemicals to pass between the epithelial cells and enter the bloodstream.

This condition is known as increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut.”

Increased intestinal permeability triggers local inflammation, accumulation of white blood cells, and release of substances that further fuel inflammation (histamine, serotonin) [11].

These inflammatory substances negatively affect the nervous and muscular systems of the gastrointestinal tract. As a result, spasms occur in some parts of the intestine, while in others, normal motility decreases.

The outcome is abdominal pain, altered intestinal transit, and episodes of diarrhoea or constipation.

Part of the bloating and abdominal distension experienced in IBS is due to increased gas production during digestion.

Normally, gases such as hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane are produced as part of normal digestive processes.

However, changes in the intestinal microbiota and increased consumption of foods such as sugar, alcohol, processed flours, and certain fruits and vegetables lead to excessive fermentation and overproduction of intestinal gas, further aggravating distension and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Diet

One of the primary strategies used by people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) to manage their symptoms is dietary modification. Until recently, the standard therapeutic approach focused on avoiding foods that provoke symptoms and excluding gluten [9,11].

We know that certain foods can cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as gas, diarrhoea, bloating, and abdominal discomfort. Such foods include milk and other dairy products, legumes, certain vegetables such as broccoli, some fruits, and cereals—particularly wheat [12].

Many of these foods are considered “gas-producing” and are commonly recommended for avoidance in cases of excessive flatulence and bloating. Previously, these foods appeared on general avoidance lists without classification based on their biochemical components.

However, in recent decades, the specific compounds responsible for these reactions have been identified [11,12]. These are a group of sugars collectively referred to by the acronym FODMAP.

The diet developed to reduce them is called the “Low FODMAP Diet” and has shown excellent results in managing IBS symptoms [9,11].

Low FODMAP Diet

FODMAPs are a group of short-chain carbohydrates found in many foods such as wheat, dairy, fruits, legumes, vegetables, nuts, and sweeteners.

F – Fermentable: carbohydrates that undergo fermentation

O – Oligosaccharides: sugars found in some fruits, legumes, and dairy

D – Disaccharides: such as lactose

M – Monosaccharides: such as fructose

A – And

P – Polyols: sugar alcohols such as sorbitol, maltitol, erythritol, and xylitol

These are sugars that the small intestine cannot fully digest and absorb. As they pass into the large intestine, they draw water and undergo fermentation by gut bacteria, producing gas and increasing intestinal pressure.

The increased amounts of fluid and gas in the intestine lead to bloating and changes in the speed of food transit. This results in gas, pain, and diarrhoea. Reducing intake of these carbohydrates can significantly alleviate symptoms.

Clinical studies show that a low-FODMAP diet improves IBS symptoms, with 76% of patients reporting improvement after following the diet [9].

Foods High in FODMAPs

Lactose:

- Cow’s milk, commercial yoghurt, creams, ice cream, cottage cheese, anthotyro, ricotta, mascarpone

Fructose:

- Fruits such as apples, pears, peaches, cherries, mangoes, and watermelon.

- Sweeteners such as honey, agave nectar, molasses, and jams.

- Products containing high-fructose corn syrup.

Fructans:

- Wheat, garlic, onion, rye, watermelon, cashews

- Vegetables such as artichokes, asparagus, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, beets

- Cereals/flours such as wheat, rye, spelt, barley, and related pasta

- Nuts such as cashews and tahini

- Added fibre such as inulin

Lacto-oligosaccharides:

- Chickpeas, lentils, beans, soy products, broccoli

Polyols:

- Fruits such as apples, apricots, blueberries, cherries, nectarines, pears, peaches, plums, and watermelon

- Vegetables such as cauliflower, mushrooms, peas

- Sweeteners such as sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, maltitol, and isomalt, found in sugar-free gums, candies, and cough syrups

Foods Low in FODMAPs

Dairy:

- Almond milk, coconut milk, homemade 24-hour fermented yoghurt, hard cheeses such as feta and brie

Fruits:

- Blackberries, kiwis, lemons, oranges, strawberries, melons, grapefruit, bananas

Vegetables:

- Carrots, cucumbers, ginger, lettuce, olives, aubergines, chives, bamboo shoots, Chinese cabbage, spring onions, turnips

Protein:

- Beef, lamb, goat, pork, chicken, fish, eggs, prosciutto

Nuts (up to 10–15 pieces):

- Almonds, macadamia nuts, pistachios, pine nuts, walnuts

Cereals / Seeds:

- Oats, oat bran, rice bran, gluten-free pasta (buckwheat, quinoa), white rice, buckwheat flour, quinoa

The principle of the Low FODMAP Diet is to limit only the problematic foods within each category, not to exclude all.

The diet should be followed under the guidance of a qualified dietitian. Initially, all FODMAPs are eliminated. They are then gradually reintroduced one by one, while symptoms are monitored. Each individual may tolerate certain foods better than others. Moreover, many of these foods are beneficial to health.

It is noteworthy that FODMAPs often have a prebiotic effect, serving as nourishment for beneficial gut bacteria and helping regulate the intestinal microbiota [13].

Gradual reintroduction in small amounts allows growth of bacteria capable of metabolising these sugars, improving tolerance and dietary diversity over time.

Probiotics

The intestinal flora plays vital roles not only in intestinal function but also in overall health, including:

- Nourishing the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa

- Maintaining normal intestinal pH

- Supporting digestion and nutrient absorption

- Regulating intestinal motility via serotonin and other neuroactive substances that act on the enteric and central nervous systems

- Modulating immune system activity

Alteration in the composition of the intestinal flora plays a decisive role in the development of irritable bowel syndrome. Patients with IBS typically show a reduced presence of beneficial bacteria and overgrowth of pathogenic microbes [11] [14].

A significant number of studies have highlighted the beneficial effect of probiotic administration. Probiotics significantly improve symptoms such as bloating, constipation, diarrhoea, and abdominal distension [15] [16] [17].

Evidence further shows that multi-strain probiotic preparations yield superior results compared to those containing a single bacterial strain [18].

Deficiencies Associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome – Vitamin D, Zinc, Glutamine

Zinc

Individuals with IBS often require medical supplementation, either to correct common deficiencies associated with intestinal dysfunction or to use therapeutic doses of micronutrients that alleviate symptoms.

A common deficiency is zinc. Zinc is essential for the normal functioning of the immune system and nervous system and for maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosa.

Zinc also contributes to the synthesis and secretion of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine, which regulate nervous system activity.

Therefore, zinc deficiency may be associated with hyperactivity, difficulty sleeping, concentration problems, and increased pain sensitivity.

This deficiency perpetuates the syndrome's underlying mechanisms and negatively impacts the psychological aspects of the disease [3].

Additionally, zinc deficiency causes disturbances in intestinal motility and negatively affects the intestinal flora, the ability of the mucosa to heal, and the management of inflammation.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D deficiency is common among individuals with IBS. It is essential for the proper functioning of tight junctions, and supplementation has been shown to reduce intestinal permeability [19].

Increasing evidence indicates that vitamin D supplementation significantly improves abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhoea, constipation, and quality of life in IBS patients [4–6].

Testing for vitamin D deficiency is therefore highly recommended for all patients with IBS. A study published in Nature – European Journal of Clinical Nutrition reported that the vast majority of IBS patients benefit from vitamin D supplementation [4,5].

Glutamine

Glutamine is an amino acid. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins in the body.

Glutamine is essential for the proper functioning of the intestinal mucosa and serves as the primary fuel source for intestinal and immune cells [19].

Although normally synthesised by the body, deficiency can occur under conditions of physiological or psychological stress, such as:

- Infections

- Intense physical exercise

- Severe emotional stress

- Radiotherapy or chemotherapy

- Serious injury

- Postoperative recovery

Multiple studies confirm that glutamine supplementation reduces intestinal inflammation [19].

Recent clinical data show that it can safely and effectively improve symptoms in post-infectious IBS [20].

Nutrients not only support growth and survival but also play a vital role in maintaining the normal function of the intestinal mucosa.

Extensive research demonstrates that nutrients such as vitamins, probiotics, amino acids, minerals, and fatty acids:

- Help maintain the integrity of the intestinal epithelium

- Regulate the epithelial barrier function

- Support balanced immune activity within the intestine

Targeted supplementation with these nutrients improves mucosal function and helps restore gut health in individuals with gastrointestinal disorders [19].

Specialised Tests Detect Deficiencies in the Body and Disorders in the Intestinal Flora

Comprehensive lab testing that assess several functions of the body now provide a much more accurate picture and identify:

- Deficiencies in zinc, amino acids, vitamins, and other vital micronutrients essential for healthy intestinal mucosal function

- Disturbances in the intestinal microbiota and deficiencies in beneficial probiotics

- Metabolic disorders that promote chronic inflammation and worsen the clinical picture of irritable bowel syndrome

These tests are not routinely performed during standard checkups. They are highly specialised and can detect metabolic dysfunctions caused by disease, providing an accurate assessment of each individual's overall health status.

These tests provide precise data on micronutrient deficiencies and metabolic dysfunctions.

This information enables targeted interventions in lifestyle and nutrition, leading to long-term, clinically significant improvements in most cases.

While no single approach produces permanent results, modern root-cause care offers multiple tools that can achieve sustained, long-term improvement in spastic colitis. Effective care requires more than symptom control.

It must address the underlying metabolic factors that both trigger and sustain the condition.

Assessing each individual’s metabolic profile through specialised testing and developing personalised care plans to correct metabolic disorders and deficiencies have been shown to relieve symptoms and promote overall health restoration [21,22].

Conclusions

IBS is a multifactorial condition, making it virtually impossible to resolve by addressing a single cause.

Many individuals attempt to manage symptoms by avoiding one or more specific foods, but this approach does not repair the altered intestinal flora or prevent other consumed foods from containing compounds that aggravate symptoms.

The possible combinations are virtually infinite and make it particularly difficult to achieve long-term improvement. Over time, individuals give up trying to improve their bowel function and decide that they have to live with it.

However, IBS is no longer unsolvable. With targeted interventions in lifestyle, diet, and correction of nutrient deficiencies, most cases can achieve long-term, substantial improvement.

Bibliographic References

[1] Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) Medscape, updated: Dec 11, 2019. Jenifer K Lehrer, MD; Chief Editor: Anand, MD.

[2] Irritable bowel syndrome. Symptoms & causes. Mayo Clinic. Jul 2020.

[3] Nutritional Deficiencies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A North American Population-Based Study. Hujoel, Isabel A. Mayo Clinic Rochester, MN. American Journal of Gastroenterology: October 2019.

[4] Vitamin D status in irritable bowel syndrome and the impact of supplementation on symptoms: what do we know and what do we need to know? Claire E. Williams, Elizabeth A. Williams & Bernard M. Corfe. Nature, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Jan. 2018.

[5] Vitamin D supplements could ease painful IBS symptoms. Science Daily 2018.

[6] Vitamin D associates with improved quality of life in participants with irritable bowel syndrome: outcomes from a pilot trial. Simon Tazzyman et. al. Dec 2015. BMJ Open Gastroenterology.

[7] Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients Sept. 2019. Hanna Fjeldheim Dale et. al.

[8] Effectiveness of Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Updated Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis Tina Didari et. al. World J Gastroenterol. 2015

[9] Try a FODMAPs diet to manage irritable bowel syndrome. Harvard Health, September 17, 2019.

[10] Diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Magdy El-Salhy, Doris Gundersen. Nutrition Journal. Springer Nature, 2015.

[11] Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Alexander C. Ford, M.D., Brian E. Lacy, M.D., and Nicholas J. Talley, M.D., Ph.D. N Engl J Med 2017.

[12] History of the low FODMAP diet Peter R Gibson. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Mar.

[13] Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic Mary Ellen Sanders, Daniel J. Merenstein, Gregor Reid, Glenn R. Gibson & Robert A. Rastall. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

[14] Management of Chronic Abdominal Distension and Bloating Brian E. Lacy et. al. Clinical Gastrenterology & Hepatology. April 01, 2020.

[15] American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et. al. Am J Gastroenterol 2014.

[16] altered molecular signature of intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis Hai-Ning Liu Hao Wu. et.al. Digestive and Liver Disease, January 21, 2017.

[17] Randomized clinical trial: the effect of probiotic Bacillus coagulans Unique IS2 vs. placebo on the symptoms management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults Ratna Sudha Madempudi, Jayesh J. Ahire, Jayanthi Neelamraju, Anirudh Tripathi & Satyavrat Nanal. Nature Scientific Reports. 21 August 2019.

[18] Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review Hanna Fjeldheim Dale et.al. Nutrients . 2019 Sep.

[19] Intestinal Permeability, Inflammation and the Role of Nutrients Ricard Farré et. al. Nutrients. 2020 Apr.

[20] Randomised placebo-controlled trial of dietary glutamine supplements for postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome QiQi Zhou et. al. Gut . 2019 Jun.

[21] Metabolic profiling of organic and fatty acids in chronic and autoimmune diseases. Evangelia Sarandi, Maria Thanasoula, Chrisanthi Anamaterou, Evangelos Papakonstantinou, Franco Geraci, Maria Michelle Papamichael, Catherine Itsiopoulos, Dimitris Tsoukalas. Advances in clinical chemistry (ElsevIer) 2020, in print.

[22] Chronic Inflammation in the Context of Everyday Life: Dietary Changes as Mitigating Factors. Margină, D.; Ungurianu, A.; Purdel, C.; Tsoukalas, D; Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2020.

[23] Image credits: Gracia Lam, The New York Times